Exclusive Interview with Charlie Schaffer: Winner of the BP Portrait Award 2019

Posted by Cass Art on 29th Aug 2019

The BP Portrait Award is back for its fortieth year at the National Portrait Gallery. The prestigious painting competition brings us the very best in contemporary portraiture today; showcasing a breadth of approaches to portraiture this year’s award includes the unusual, the beautiful and the uncanny. This year’s exhibition has ranged from self-portraits, to portraits of friends, family and strangers. This year's winner was Charlie Schaffer, for his painting For Imara in her Winter Coat.

We caught up with Charlie ahead of our Face to Face exhibition in Cass Art Islington for an insight into his process, his insight into the competition and how his personal experiences with mental health has influenced his work:

Congratulations on winning the 1st prize at this year’s BP portrait award. How have you found the experience?

Thank you very much. To be honest, it was a bit of a bizarre experience. I was unfortunately very physically ill leading up to the show, essentially for the entire 3 months from the time that we found out that we had been shortlisted to the actual announcement of the prizes. I didn't mentally deal with being so run down very well - the week of the opening was one of the more intense weeks of my life (interviews, the actual adrenaline of the announcement etc.) and so it exhausted me more than I had expected, meaning that my mental health took a battering and left me in a state that I had never quite reached until then. Life works in particularly odd ways, and after a string of equally strange occurrences I managed to get myself out of that hole and return to my preferred self, one who is excited by life and all the possibilities it has to offer. So, to answer the question more directly, the immediate experience was one of deep depression, however I am now able to appreciate it and enjoy all the joy that it has given to family and friends who have been able to feel proud.

One thing I certainly learnt from this experience was that things never live up to what they claim, but it is not the event itself that is to blame, it is what you decide to take from it. This is true with all events in life, more so with ones that one sees as being larger/more important.

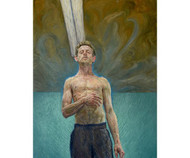

Charlie Schaffer, For Imara in her Winter Coat

Although participating in the BP Portrait Award is incredibly exciting, and going on to win a fantastic accolade, it’s also important to acknowledge the impact that such intense artistic competitions can have.

Fortunately, I have been lucky enough to win many awards over the past 5 years or so. The first one I won was the Young Artist Award at the Lynn Painter-Stainers Prize in 2014. I was still a student, and when I won I thought "wow, I'm really onto something with this painting. I'll just do some more like this!" This inevitably led to me being unable to make anything at all, as I had now put so much pressure on myself. The way I paint is one in which I have no idea how the painting will turn out. The actual pictorial point of painting a picture for me is the act of discovery - if you know what is going to happen, why do it? This means that if you try and make a picture like one that you have previously made, you are inevitably doomed to create a pastiche of yourself, something with no real life or purpose. This was a huge learning curve for me, and an invaluable one at that. I am also fundamentally contrary, which helps. So, after winning the BP Portrait Prize, I actually took a step back (for many reasons) and decided not paint any people for a while. I am now back to having sitters again, but I think avoiding painting people was essential for me to ensure that I still had control over my art and that I was necessarily doing it for myself.

Charlie Schaffer, The Artist

It can be easy as an audience member to forget the difficulties and pressures that still come even after the work is hanging on the gallery walls. What advice would you have to those wanting to apply to exhibitions and competitions such as this?

The only bit of advice I can give is this: ensure that the act of creating whatever it is that you're making is the main thing. The piece at the end of the creating process is separate to you. It is something that now has it's own life and will have it's own experiences. Being attached to the works that you have created is a dangerous road to go down - if you are too proud it will be impossible for you to go forwards and develop further; if if you are too possessive and protective you will find that you take on the stresses and strains of the painting's life. Make deep connections with your art, but form no attachments. I guess this can be said of all things.

We’ve touched on mental health briefly here, and you’re very open with your personal experiences of mental health and depression. You describe the act of being with your sitter as a ‘therapy’ and the resulting portrait of Imara is equally as open in its expression. How do you find discussing your own mental health in relation to your paintings?

Personally, I find it very bizarre that people don't talk about this more. One thing I have noticed is that men are certainly less likely to talk candidly about their mental health. I have spent time with and painted a lot of women, and I have learnt almost everything I know with regards to emotional intellect from women. I am very open, firstly because I don't see why one shouldn't be, and secondly because by talking about it one can understand what one is feeling. I still find it hard to understand what it is I am feeling at the time (something that my previous partners have always been better at knowing), but the more one talks with someone about it, the more one hears about others' experiences that will have been similar in certain regards and the more one can try and understand oneself. I think there is most certainly a fear for all people (maybe more so for men because we live in a society where men are meant to always be impressive and strong) that if one acknowledges that one is depressed, then people will either think less of them or not want to hang out with them so much. There is, sadly, a truth in this - not so much in thinking less of someone, but it can be hard to spend time with people that are in a particularly bad state and who need a lot of care. This is why painting is integral to me. Through painting the same people week in week out, you diminish the desire to impress one another, and thus far it is the only way I know in which to be fully and undeniably yourself without fear of pushing the other away. When in a relationship, depression can be toxic as it creates an unbalanced dependency. This is why therapy, or painting/sitting for a painting in this way, can be essential. If one has a dependable outlet for one's true state of self, it will ensure that one is less dependant (in a negative way) on those close to them.

I’m captivated by the emotion in your painting of Imara – it feels as though I am looking beyond a purely physical representation.

You said that you believe that the conversation between artist and sitter is essential in creating a successful portrait – do you think it is this level of knowing your sitter that brings an additional level to your painting?

I paint people because I get lonely and depressed on my own. I have never been one of those painters that can just get up in the morning and make a painting for the sake of it. The act of painting, of someone coming to sit 2 or 3 times a week, is what allows me to spend time with people. We continuously talk (the idea of a human being silent and still seems absurd to me, you may as well paint a still life), and as they are coming to sit regularly, it becomes a sort of therapy. No phones, no outside world, just two people in a room talking. We live in a society that does not permit one to just sit and converse, it always has to have a function - so although that is exactly what we are doing, the fact that I am painting the sitter is what permits us both to spend time with one another in that way. I have no idea what I am doing when I paint, and certainly no idea as to what the painting will look like. Every mark is essentially a record of the experience of me spending time with the sitter. The resulting image is just as much a self-portrait as it is a painting of the sitter. I do not care whether it looks like the sitter (although if you spend 4 months, 3 times a week, for 3 hours at a time painting someone it would be slightly odd if it did not resemble them by the end), I want to capture their life, whatever that is, and create a painting that is equally alive. Although both Imara and I were going through a particularly bad period at the time of this painting, the emotion in the picture is coming just as much from me as it supposedly is from her. The resulting painting is more of a by-product of the experience of painting someone rather than it being the primary objective.

I love the image of two people spending so much focussed time together. Painter and sitter, together in a room with no outside influence, one slowly painting the other as they both share thoughts and ideas. There is something quite magical about it. Have you always worked in this way?

This is something I only started doing in the final year of University, in Brighton, in 2014, after reading Martin Gayford's book on sitting for Freud, Man With a Blue Scarf. It spoke of how important the relationship between sitter and painter was. Up until that point I was painting purely because I was on a painting course, with no real attachment to what I was doing. I did art purely because I was contrary and wanted to break from my North-West London Jewish upbringing where everyone was an accountant or a lawyer and married the person they knew from birth and lived around the corner from where they grew up. In hindsight, I already felt like there were enough images in the world, so why on earth was I making another just for sake of it? Once I started painting my friend, Antonio, who was also in Brighton at the time, I realised that I enjoyed the aspect of spending time with someone. It was only after a few years of doing this, and having multiple ups and downs in my mental strength, that I realised that if I don't spend time with people in a meaningful way, I inevitably draw back into my own mind and become disconnected to everything around me. For me, depression is a disconnectedness to the world, an existential separation, an overwhelming apathy. It also not something to be feared - depression is not a bad thing. It can be a beautiful thing where one feels things so strongly (often too strongly) and where one grows more through these periods of difficulty than in any period of contentment. We live in a society that does not allow one to slow down and feel separate from everything. I would say this is the fault of society, not of the individual.

Charlie Schaffer, Head of Thandi

There are many artists that have explored mental health either directly or vicariously through their creative practices, indeed the brush work in your portrait at the BP Award is reminiscent to me of the marks of Van Gogh. Are these artists a great influence to your work?

I do not consciously look at any artists because of their motivations. Inevitably, if there is a piece of work that one truly connects with, then the reasoning behind its creation and the outcome are all one and the same thing, they cannot be separated, and so one will have a connection with the mindset of the artist at the time. If we separate the narrative of Van Gogh to that of his work, we will clearly see how vibrant and wonderful and uplifting his paintings are. He sought to begin love and enlightenment to the world through his paintings, but this cam from a place of melancholy and despair as he did not have the love and enlightenment in his life that he desired, and so tried in vain to bring it about through his work.

When I had just began the painting of Imara, I was obsessed with Cezanne. Cezanne was obsessed with theory, and so my paintings started to become very technical and void of emotion, but I could not see this at the time and could not understand why my paintings were so lacking. I was in a deep depression at the time, and decided to run off to Amsterdam in a futile attempt to escape my own mind. When I was there, I went to the Van Gogh museum, which is so incredibly curated that one gets a real sense of the man himself, rather than the just the resulting pictures propped up by vague art history narratives. I was standing in a room of his self-portraits, and I was listening to a piece of classical music. At the climax of this piece, I felt such a deep connection with this man who essentially just wanted to be loved, that I felt overwhelmed and burst into tears. After being made sure I was okay by all those who worked there, and then eventually making it back to Brighton, I realised that, although it may be painful. one needs to put all of oneself into a picture, the good, the bad and the ugly. Without that experience, there is no way I would have created the painting as you see it now.

And what are the essential tools that you always have in your studio and do you have any particular brands you return to?

I suppose the main features of my studio are my sitter's chairs (there are two, one red and one green) and my easel. I stand up when I paint so do not need a chair myself. I primarily use Michael Harding paints (Italian Green Umber and Rose Madder being the ones I go through the most of) and some Winsor & Newton colours (naples yellow light, terre verte). I feel that one learns which colours from which brands one prefers over the years. I have quite an extreme array of brushes, none that are particular or specific, but just whatever I seem to accumulate.

Thanks so much for your openness and your honesty Charlie. It’s been fascinating to learn more about you and your work, just one final question – after a very well deserved rest, what’s next on the horizon?

Now that I have my strength back, all that I want to do is paint. I don't know when my next down period will be, or if I will have one at all, so for now I just want to make the most of being healthy and having energy. I plan to move to London in Autumn, although even with my prize money it still seems financially impossible.