Exhibition Review: Abstract Expressionism Royal Academy of Arts

Posted by Cass Art on 3rd Jun 2018

The Royal Academy of Arts presents over 150 paintings, sculptures and photographs in the first major exhibition of Abstract Expressionism to be held in the UK in almost six decades.

The selection of work aims to challenge our perception of Abstract Expressionism as a unified movement, but rather illustrate its reality as a highly complex, fluid and many-sided phenomenon.

From the ‘colour-field’ painters to the ‘gesture’ or ‘action-painters’ spanning from the early 1930s to late 1980s, journey through the pioneers of abstraction, such as Pollock, de Kooning and Rothko, to the lesser known, but still highly visual artists exploring expressionism through photography, drawing and sculpture.

We stepped behind the scenes with Co-Curators Dr David Anfam and Edith Devaney to find out more about the artists, their lure to abstraction and how the RA set out to view the selection through a 21st century lens…

Image Credit: Willem De Kooning , Woman II, 1952. Oil, enamel and charcoal on canvas, 149.9 x 109.3cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller, 1995. Â © 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London 2016. Digital image (c) 2016. The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

Early Works

Abstract Expressionism burst onto the scene shortly after the Second World War in the early 1930s. Highly active across the West Coast of America, artists grappling with figuration started to move away from realism. “Figuration is very large here,” says curator Edith. “[The works] comment on how the artists saw themselves and the complexity of developing their own style within this emerging genre.”

This shift is where the exhibition begins, with the artist’s early works acting as a springboard into how these artists individually developed throughout the 1930s as different influences came to bare on them.

Greeting us in the forecourt and interspersed throughout the exhibition, David Smith introduces a constant 3D element to abstraction. The Courtyard display seeks to recreate the spirit of Smith’s installations in his fields at Bolton Landing in upstate New York. There, not only did each sculpture enter into a subtle dialogue with others, but they also responded to the space and sky around them.

The sculptures themselves compliment the cascading shapes mirrored in the paintings, breathing a more tangible experience of abstraction as the paintings peek between the metal.

Image Credit: David Smith, Star Cage, 1950. Painted and brushed steel, 114 x 130.2 x 65.4cm. Lent by the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. The John Rood Sculpture Collection. (c) Estate of David Smith/DACS, London/VAGA, New York 2016

“He insisted his practice sit among the painters” says David, which is unescapable as his works hold the central space throughout the exhibition.

Smith created work that spanned a great range of themes and effects, and often his imagery and ideas paralleled concerns seen throughout the show as a whole.

The exhibition houses a series of both thematic rooms and Monographic galleries dedicated to the pioneers; Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko and Still, acting as central pillars that underpin the movement.

Image Credit: Water of the Flowery Mill, 1944. Oil on canvas, 107.3 x 123.8 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (c) ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016. Digital image (c) 2016. The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Arshile Gorky

Arshile Gorky’s remarkable understanding of the complexity of art ensures his presence within the exhibition. Fusing together movements such as cubism and surrealism, he developed altogether a new kind of art, grounded within his practice as a remarkable colourist.

“He had a new way with grappling with paint” says Edith, “soaking the canvas and allowing paint to drip, of which you see an impact on other artists.” This is particularly evident in Gorky’s mature works, such as ’Water of the Flowery Mill’ and ‘The Unattainable’.

Among the painted works are a series of drawings on paper. These lesser known pieces show Gorkey as the remarkable draftsman he was. Through thinned paint and precise tools, it allowed him to include the texture of the surface in his works. “His pencils were sharpened so much, that it would in fact cut the paper,” comments David.

Jackson Pollock

‘Jackson broke the eyes’ Willem de Kooning

Jackson Pollock rapidly developed his concern with the process of painting, laying the raw canvas on the floor and directly dribbling and pouring pigment with surprising control.

“Pollocks pouring [is seen as] being straight jacketed, making his work much the same” comments David. “Yet Pollock became ever more diverse, with two totally different ways of handling line which we can see evidence here. In one, its much more like calligraphy, in the other, more broader styles with an enormous range.”

Image Credit: Blue poles, 1952. Oil, enamel and aluminium paint with glass on canvas, 212.1 x 488.9 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. (c) The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016

When the art collector Peggy Guggenheim commissioned Jackson Pollock in the summer of 1943 to paint a mural for her Manhattan townhouse, the resulting canvas - the largest that Pollock would ever create - became a titanic early milestone in abstract expressionism.

The seismic impact of ‘Mural’ in 1943 lead to Gorkey creating his largest painting of his career in the following year, with the biggest art critics, artists and curators visiting Peggy’s Manhattan townhouse over the subsequent years, defining a sizeable shift in artworks scale.

His later work “Blue Poles” is showcased on the opposing wall to “Mural”, acting as bookends to his short, but highly influential career before his death in 1952.

Image Credit: Lee Krasner, The Eye is the First Circle, 1960. Oil on canvas, 235.6 x 487.4 cm. Private collection, courtesy Robert Miller Gallery, New York. (c) ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016

Gestures as Colour

Defying categorisation into ‘colour-field’ artists versus ‘gesturalists’, Philip Guston, Joan Mitchell and the young Helen Frankenthaler evolved their own respective pictorial syntheses by the end of the 1950s.

Figurist, but highly coloured paintings, the works in Gallery Four explore artists outside of the ‘key players’ of expressionism.

Joan Mitchell’s highly worked brush work on canvas and Helen Frankenthaler’s oil washes staining the canvas boldly highlights each artists’ own unique fusion of colour and gesture.

“Janet Soble started painting when she was in her 40s, taking her children painting materials she painted remarkable works” comments Edith.”Pollock saw her in ‘The Art of the Century’ at the Guggenheim, and her influence can be seen to some extent with Pollock’s larger canvases.”

It was also within this period that Mark Rothko met Clyfford Still, and they both began teaching at the California School of Fine Art. This is where you can see “Rothko make his breakthrough into abstraction,” says David. “These, first multiform canvases were on the very cusp of what became Rothko’s classic style in the 50s.”

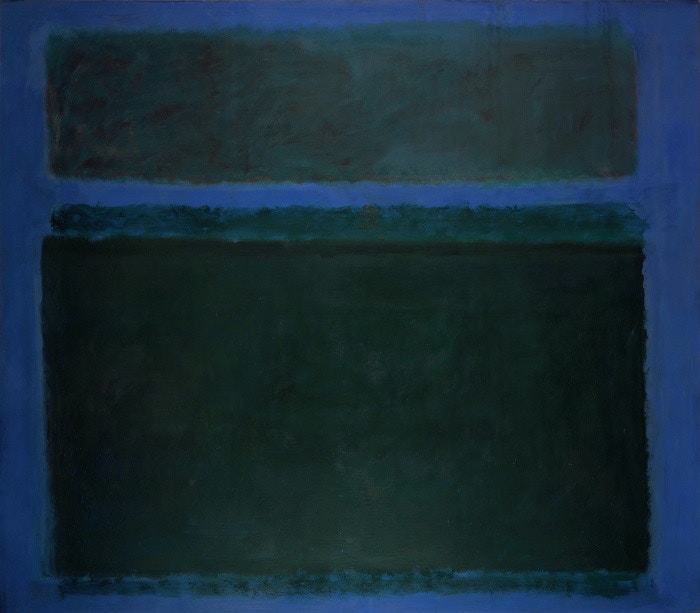

Image Credit: Mark Rothko, No. 15, 1957. Oil on canvas, 261.6 x 295.9 cm. Private collection, New York. (c) 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko ARS, NY and DACS, London.

Willem de Kooning & Mark Rothko

Alternating between abstraction and the figure, Willem de Kooning’s fixation with the female presence continued throughout his career. From the claustrophobic realms of female sexuality to the undercurrents of lust and damnation to salvation within eroticism, much of de Kooning’s work was encoded with a feminist iconography.

The early landmark painting ‘Pink Angels’ that situated such female fixations rapidly lead to an opposing theme, in the lacerating shards that comprise the haunted nocturne of ‘Dark Pond’. Throughout his work, de Kooning never stops losing the figure. “de Kooning never stopped being an easel painter,” discusses Edith. “Which lends the scale of his works to never exceed the stand.”

This abstraction of deep, almost carnal emotions are embodied in Mark Rothko’s iconic paintings of the 1950s and ‘60s. His paintings, the abstract embodiments of ‘tragedy, doom and ecstasy’ are instantly recognisable through their tiers of hovering rectangles.

“Rothko called his paintings ‘facades’, a word that captures their enigmatic hypnotism,” says David. “Rothko’s silence is so eloquent - the language of emotions in abstract forms.”

The layers of darkness were sometimes flecked with tiny speckles of white, adding a subtle shimmer, an iridescence, to the painting, alluring to the complexity of human emotions.

Image Credit: Franz Kline, Vawdavitch, 1955. Oil on canvas, 158.1 x 204.9 cm. Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Claire B. Zeisler 1976.39. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016. Photo: Joe Ziolkowski

Barnett Newman & Ad Reinhardt

Much like Rothko, Barnett Newman used block colour to summon feelings on a immense scale, using an empowering blue featuring in multiple works, including ‘Ulysses’, ‘Profile of Light’ and ‘Midnight Blue’ to render feelings of intense, oceanic immensity. Pushing colour to the extremes, both Newman and Reinhardt were profoundly different. “There was no cohesiveness to the way they painted” says Edith.

Clyfford Still

The penultimate galley houses the rarely seen work of Clyfford Still. Comprising 10 enormous canvases, generously donated by the Clifford Still Museum in Denver, which houses over 95% of the artist’s collection.

Living and working in Washington State, Still was somewhat detached from the expressionists who found fame in New York. “Growing up on the baron, desolate prairies of Alberta, he often went his own way, which in part explains his originality,” explains David. “He associated the ascendant verticality with the dominance in many of his compositions with the life force, quite literally realised here as vertical lines.”

Image Credit: Clyfford Still, PH-950, 1950. Oil on canvas, 233.7 x 177.8 cm. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver (c) City and County of Denver / DACS 2016. Photo courtesy the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO

His deep relationship with the land’s ‘awful bigness’ reflects a simple geographical fact: his sheer remoteness from the wider art world. Rendered with a palette knife, his layers of luminosity and darkness heightens this sense of drama and intensity. “These are not paintings in the usual sense” explains David, “They are life and death merging in fearful union.”

Late Work

The final space shows that in their late work, the abstract expressionists went out not with a whimper, but with a bang. As more symbolic, contemporary references began to influence abstractionists everywhere, the final space brings together works which show an embodiment of this new vibrancy. The room is filled with dynamic paintings exploring light, colour and dynamic brush work, centralising on nature as red seas, tinted mist and bold floral shapes the space.

This celebration of colour and spontaneity is seen in Hans Hoffman's late canvases and Joan Mitchell’s 'Salut Tom'; matured with light, reflections and airiness, a series of welcomed brights after the intensity of ‘Darkness’ and Rothko’s mood paintings.